Context

Definition

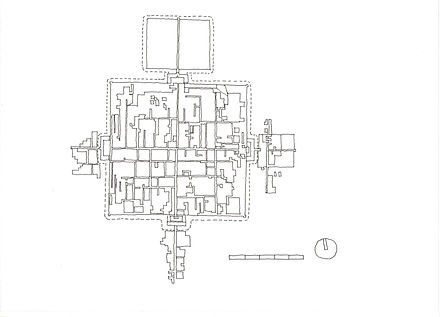

Nam Pin Wai, a village within a dense urban context.

There are 70-80 walled villages remaining in Hong Kong (note 1).

There are 652 “recognized villages” on the list maintained by the Hong Kong Director of Lands (note 2). This is a specific definition vital to contemporary legal rights, the Hong Kong village being traditionally occupied by a clan of single surname, organised in a patrilineal structure following the eldest male descendant. Villages of several types can be found in the New Territories. They may be compact (as walled villages are), linear or dispersed (note 3).

Different authors identify different numbers of walled villages, based on their criteria for selection. A common categorisation stems from village name, where Wai equals “walled village”. Ip (1995) rather concludes that Wai does not necessarily confirm the presence of a wall and also points out the existence of several Tsuen and Uk walled villages, concluding that Wai denotes a significant settlement, Tsuen one with less social status, and Uk a walled house or family settlement.

The definition of “walled” is therefore approximate because many formerly walled villages have lost their enclosure, and can now be applied to those villages with a characteristic rectangular plan and positioning of gatehouse and shrine (note 4). Villages with walls exist which are not included on any list, for example Ha Tsuen Shi (Yuen Long). Developments and extensions occasionally subsume the original village enclosure, rendering the original layout almost indistinguishable on the ground, for example at Nam Pin Wai (Yuen Long).

Notes:

-

Of the 70-80 listed walled villages, Ip (1995) lists 71, Wikipedia (2018) lists 79. Ip lists 5 not in Wikipedia. Wikipedia lists 11 not in Ip. Both lists include Nga Tsin Wai Tsuen (now demolished). Wikipedia lists Ho Sheung Heung as a single village but notes it is composed of four. Wikipedia also lists Sam Tung Uk, now a museum, not listed by Ip. Neither include Ha Tsuen Shi (Yuen Long). Ip refers to Siu (1990), who lists 48, based on the instance of wai in the village name, but later disproves this as a criterion. Hayes, (2001) quoted in Shelton (etc, 2011) estimated there were 23 walled villages prior to WWII.

-

For the 652 recognized villages see HK Lands (2009).

-

For different village typologies see Ip (1995), with diagrams

-

For a more detailed discussion of walled village definition see Ip (1995). The definitions interestingly follow those outlined by Hoskins in The Making of the English Landscape (1955).

Origins

Clans and their Migrations

The New Territories became inhabited as a series of migrations, initially by Han settlers from the 10th century, around Kam Tin. The earliest villages established in the 10th to 11th centuries were clustered in the fertile valley bottoms of the northern New Territories around Ho Sheung Hung, Fanling and Sheung Shui. Migration continued into the 14th century, though these later settlers were left to occupy the less profitable land, such as San Tin, a marshy plain at the time, or Ho Chung, a hilly region with scattered plots of flat land (note 5). The area prospered, with village clusters and markets the focus of rural trade. These early migrants from the north were organized as clans, usually based on shared surnames, and marked their status by the name Punti, or Bendi, or To Chu, meaning “aboriginals” (note 6). The Hakka in particular underwent five major migrations from the 4th century to the late 19th century; Hakka peoples inhabited the northern plains of China until successive invasions in the 4th and 9th centuries forced their migration into the southern mountains (note 7). The word Hakka means “guest people”. By 1573 the new Xinan government recorded 74 villages (note 8).

The chaos of the Ming-Qing transition saw destruction of the original settlements, in particular the Coastal Evacuation of 1662, ordered by the Qing government for defensive reasons. The evacuation was rescinded in 1669, but whilst the Punti reclaimed their original lands, many did not return (note 9). In order to bring prosperity Hakka clans from Guangdong, Fujian and Jiangxi were encouraged to settle in the area. Returning Punti and immigrant Hakka clans established today’s walled villages around this time. Villages of returning Punti clans tended to be founded on better quality land in the west, established in prosperous clusters, whilst those of Hakka immigrants tended to be located on difficult terrain further east with limited capacity for expansion.

Han pottery house models in Hong Kong Museum of History, from Hong Kong Lei Cheng Uk Tomb, AD25-220, and Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, UK, from Guangdong 200BC-AD200. The Han brought their architecture with them.

Clustering and Dispersal

Villages can be single or multi-surnamed. The most powerful are clan settlements where everyone is related through patrilineal descent, the powerful clans (Tang, Hau, Pang, Liu, Man, To) accounting for 30 of the 45 single surnamed occurrences. This power is reflected in the standard of construction of single surname villages, for example in the use of expensive grey brick rather than clay lump adobe. Single surname settlements would have adequate manpower to obtain resources, organise defence and resist attack. Multi surname settlements by contrast lacked human and financial resources to prosper and defend themselves and resorted to the support of other lineages; they were also susceptible to fluctuations in the dominant family and struggles for power and control of land. Multi-lineage clusters would consist of separate enclosures, protection developed from social conflict. These kinship processes help explain the clustering and dispersal of villages in the New Territories (note 10).

Heung Alliances

Culturally, larger villages and clusters of villages were founded by more powerful single clan lineages, whereas weaker or multi lineages are found in dispersed villages with no clear focus. Initially Hakka settled in the eastern New Territories, as distinct from established Punti settlements further North, but gradually these assimilated, with the spread of Hakka migrants, village groups of mixed Punti-Hakka origin and alliances against the powerful families. Hakka villages were still being established well into the 20th century, but these were often as squatter settlements on poor land or with poor communications. The cluster, or heung, became paradoxically both a mutual support system and a setting for feuding and struggles for supremacy, with elite lineages controlling land ownership, markets and all transport. The district of Shap Pat Heung literally means eighteen villages. There is no cluster of Hakka villages as there is Punti (note 11).

Dominant lineages established regional alliances (yue) to protect their economic interests by offering protection to satellite villages in their territory. Non-aligned villages and those of mixed clan would also form alliances. These alliances would offer protection and continuity of shared irrigation systems, evolving into local community political groups (note 12). The villages of Lam Tsuen were linked by the Luk Wo Tong alliance, replaced by a modern committee (note 13).

Mutations

Successive mutations took place, new villages being founded as populations increased. From settlements in Tuen Mun Tai Tsuen, the village of Tuen Tsz Wai (Tuen Mun) was founded in the early 18th century, but later dispersed into 5 clan villages. The Tangs of Fanling expanded from Lung Yeuk Tau to surrounding areas founding 11 villages known as the Five Wais and Six Tsuens. The Mans first settled in Tai Po, then Tai Hang initially at Tze Tong Tsuen, but as clan numbers increased they built again at Fui Sha Wai and Chung Shum Wai. The Yeungs settled in Kuk Po Lo Wai in the 17th century then branched out to four other co-located villages. Sheung Cheung Wai (Ping Shan) was originally built with “hovels” for the Tang’s servile families, who were evicted and replaced by an expanding Tang clan in the 19th century (note 14).

An incoming clan might upset the feng shui of a village. The occupants of Sheung Wo Hang (Sha Tau Kok), the Ho, Tsang and Tang, considered the feng shui of the ancestral hall of the newly arrived Lee clan so harmful they left the village to establish others nearby (note 15).

The Heung, a cluster of villages. Sheung Shui Heung, formed of 8 villages. The Five Wais of Fanling.

The Heung. Expansion of the Tang clan in Yuen Long Kau Hui. Nam Pin Wai (A) and Sai Pin Wai (B) were originally occupied by the Tang in the 17th century. Sai Pin Wai later became multi-clan. Soon after the Tang expanded to Ying Lung Wai (E), and joined the multi-clan Tung Tau Tsuen (C). Tai Wai Tsuen (F), originally founded by the Wong and Choi, was also occupied partly by Tang, but it appears that Tsoi Uk Tsuen (D) remained a Choi village.

Date of foundation

The establishment date of most villages is often noted under its AMO listing. Of foundation dates listed by AMO (note 16), 23 are pre-Coastal Evacuation (probably re-colonised and rebuilt in the late 17C), 31 are late 17C, 16 are between c1700 and 1933; 12 are not stated.

Villages of later foundation and changes to earlier villages, with lower walls, fewer towers and less extensive moats, suggests a decreasing need for defensive features (note 17). The sequence of building is thought to have varied according to the perceived threat at the time. Either the walls, gatehouse and shrine were built first as an empty shell, to be fitted out with houses later, or walls and gatehouse were added to an established village, sometimes as part of a later village expansion (note 18).

Attack and Defence

Pirate and bandit attacks on these settlements were insistent; whilst there are official records from the 14th century, they probably pre-dated this time. Hase (1999) quotes several attacks in the mid 16th century. Piracy continued until 1850, and bandits were still raiding in the late 1940’s. Banditry, kidnapping and assaults continued through the 1950’s. In the constant power struggles over land ownership, conflicts between rival Punti and Hakka clans were commonplace, and continued long after piracy had been eliminated (note 19). Following the British occupation of the New Territories, the walls proved less effective in the face of imperial gunboat diplomacy; Wesley-Smith (1973) relates two incidents in Kam Tin in June 1898 and April 1899, the first when a British party forced entry with 75 marines and two Maxim guns, the second when the walls were blown down either side of the gatehouses of Kat Hing Wai and Tai Hong Wai forcing the villagers to surrender (note 20). Hase (1999) notes the gates of Nga Tsin Wai were barred for the Riots of 1967.

In addition to attack from rival clans, bandits and pirates, villages would offer protection from wild animals such as wild boar, civet cats, porcupines and bears, most of which have retreated in the face of urbanization. The South China Tiger, now considered extinct by the WWF, roamed the New Territories into the 20th century, when attacks were recorded (note 21). Protection from ghosts was also important, dealt with by correct feng shui.

A local security force (xunding), often referred to as Gang Lin, and sometimes armed with guns, would be organised by the village or cluster to protect the community including ritual and political territory, particularly at night. This practice continued into the 1980’s (note 22). As anyone who has toured the New Territories today will testify, unchained village dogs can be a powerful deterrent, friendly to residents whose scents they recognize, less so to strangers.

There is no evidence villages were laid to siege for periods, nor that siege tactics were employed such as undermining of corner towers. Attacks tended to be short-term raids on goods and livestock by pirates or rival clans, the attackers having no interest in acquiring the village or land. Weapons would be small portable canon and guns (note 23). Intruders were fought off with guns, iron rods, rocks, and hot fire ashes (note 24).

Notes:

5. Notes on migrations derived from Ip (1995)

6. Notes on clan etymology derived from Poon (2009),and Watson+Watson (2004)

7. Notes on Hakka migrations Sullivan (1972).

8. 74 villages source, Hong Kong Museum of History.

9. The CE evacuated all inhabitants within 50Li (25km) of the coast, its aim to deprive anti-Manchu forces of sanctuary amongst the population (Watson+Watson, 2004). Ip (1995) quoting Hayes, states that 1,648 returned from an original population of 16,000. Watson+Watson (2004) on the other hand state that the Tang, Man and other groups quickly returned to reclaim old territory and claim new, calling this a “scramble for land in the years after 1669”.

10. Notes on clan settlements derived from Ip (1995) and Sullivan (1972).

11. Notes on alliances derived from Ip (1995), Wesley-Smith (1994), AAB List (2018)

12. Notes on groups derived from Liu (2003), Watson+Watson (2004).

13. Notes on Lam Tsuen derived from AAB List (2018)

14. Notes on mutations derived from AAB List (2018)

15. Notes on Sheung Wo Hang derived from AAB List (2018)

16. AMO foundation dates see Hong Kong AAB (2018).

17. Notes on later villages derived from Wang (1998)

18. Notes on morphology derived from Ip (1995)

19. Notes on piracy derived from Ip (1995). Poon (2009) highlights in particular the Punti-Hakka Clan War conflicts of 1854-67, stating that 2,000 villages were devastated during this period. Watson+Watson (2004) state, “it was not uncommon for whole communities to be systematically looted by roving outlaw gangs.”

20. The complete walls of Kat Hing Wai clearly show signs of periodic repair, some of which may date to this incident, or to the damage inflicted during the Japanese Occupation of 1941-45 noted in AAB List (2018). Tai Hong Wai meanwhile is now walled by modern “small house” types.

21. Notes on tigers derived from Marsh (2015), adding that sightings continued until at least 1965. Hase (1999) notes the practice of shuttling goods from Nga Tsin Wai to Sha Tin in armed convoys using gongs and conch shells to frighten the tigers.

22. Notes on defence force derived from Liu (2003), AAB List (2018). Watson+Watson (2004) add that subservient villages were prevented from forming a guard in case they became rivals, and that the heung district forces were themselves responsible for much personal violence in ensuring dominance of the clan lineage.

23. Notes on attacks from personal interview, Ng (2019)

24. Defence tactics notes from AAB List (2018), for Fui Sha Wai.

Location

Land with Good Farming Potential and Auspicious Feng Shui

A good location for a village might be a coastal plain, with access to fishing aswell as farming, and in a sheltered bay or sea channel away from waves. Tai Po combines these benefits with a reliable water supply, so hosts a number of settlements. Villages in the Northeast had restricted natural farming land, but practised reclamation. The extensive flat fertile plains of Yuen Long, Fanling, Sheung Shui, Kam Tin, Shek Kong, Lam Tsuen, Tai Hang, and Ping Yuen supported many sustainable villages with reliable water supply, often in clusters, and with good access to markets. In Kowloon, Nga Tsin Wai was located alongside established salt industries under the protection of the Salt Intendant and guard (note 25). On more difficult terrain, in small valleys or on hill slopes, more recently established villages tended to be smaller, isolated, marginal and short-lived.

Feng shui is an ancient practice guiding the planning principles of both the living and the dead, bringing good fortune by correct placement in the environment. Initially it can be used to find the best location for a building or settlement. In Southeastern China the preferred sites would have:

-

Mountains on three sides, the front never blocked

-

Mountain on the left slightly higher than mountain on the right

-

Vegetation on the mountain behind

-

Gentle bends of watercourses in front, not rapid flow or sharp bends

-

South facing orientation

There is a practical purpose to many feng shui principles, based on proper ventilation, drainage and daylight in sites and buildings. Knapp (1986) notes that feng shui literally translates to “wind and water”. These remain its principal concerns. Hills to the rear (north) do not block the sun and guard the rear, and would protect the site from winter cold northerly winds. Trees would substitute for mountains to the rear, functioning also as a windbreak. A south or south easterly aspect for all houses would be optimum orientation for cooling summer breezes. Facing the sun was considered auspicious as it signifies the source of hope, energy and wisdom. The avoidance of marshy areas in favour of sites where drainage takes standing water away would guard against mosquitos and malarial disease, whilst avoidance of fast moving rivers would reduce the risk of flooding, hence a slow moving watercourse was preferred. A large pond at the front, as at Fanling Wai, would satisfy a feng shui requirement and moderate the ambient temperature of a site through cooling incoming breezes. These rules were not universal because of the great range of topographic conditions and were implemented more as rules of thumb; for villages with no immediate hills or streams around the site, substitute reference points would be used, such as a grove of trees to the rear and a clear view to mountains to the front (note 26). Such micro concerns explain the different orientations of neighbouring villages.

Feng Shui. A feng shui master determines the ideal site and orientation in a Chinese woodcut illustration. For good chi, wooded hills to the rear, the highest to the left, well drained ground, and a slow moving watercourse in front. Sketch of Tung Kok Wai, the village backed by the wooded hills of Lung Shan. Car parking at Tai Tseng Wai, though much changed, has a running stream and background hill Kai Shan, the gatehouse is visible just right of centre.

Farming

Traditional economies were based on agriculture and fishing, together with rural industries such as lime-burning, firewood, and salt production. Local workshops produced sugar from cane. Coastal marshland districts reclaimed saline brackish paddies and fishponds, and engaged in oyster and shellfish collection, lime, cement, oyster sauce and salted fish production (note 27). Pearl and oyster farming was initially popular but died out in the early 17th century as over-harvesting led to depletion of stocks (note 28).

Traditional cultivation on the surrounding landscape was dominated by rice paddy fields, with over 9,000 hectares of paddy fields remaining into the 1950s (note 29). In this region the growing season is much longer allowing for profitable double cropping in June and October on well irrigated farmland, whereas “dry paddy” on hilly areas and “saline paddy” on coastal marsh would yield only one crop per year (note 30).

Markets

A market was usually co-located with a village or easily accessible, with market towns being established by Punti clans in Yuen Long, Tai Po and Sheung Shui (note 31). The Mak clan of Pan Chung produced blue-and-white porcelain ware, exported over Southeast Asia, but also sold their vegetable produce in the local markets of Tai Po Market and Tai Wo Market (note 32). Tuen Mun San Tsuen and Lam Tei Tsuen (Tuen Mun) are co-located with the Lam Tei Market. The reliance on markets is perhaps reflected in the lack of functional diversity seen in villages, where individual shops are rarely found even today; perhaps the farming tradition has left a residual antipathy to the convenience store.

Lam Tei Market, around which are clustered the villages of Tuen Mun San Tsuen and Lam Tei Tsuen.

Notes:

25. Hase (1999).

26. Notes on feng shui derived from Ip (1995), Sullivan (1972), Knapp (1990), Knapp (1986), Poon (2009), Ho (2008), Watson+Watson (2004).

27. Notes on economies derived from Wesley-Smith (1994), Watson+Watson (2004), and Hong Kong Museum of History.

28. Notes on oyster farming derived from SCMP/Lazarus (2018)

29. Figure from HKCLSO (1966), also noted in Lung (2005), quoting Lee and DiStefano (2002).

30. Notes on cropping derived from Sullivan (1972) and Hong Kong Museum of History.

31. Source Sullivan (1972) and Hong Kong Museum of History.

32. Notes on Mak clan derived from AAB List (2018)

Some Typological Precedents

Knapp (2000) points out the complexity of migration patterns and the consequent difficulty of assigning definitive architectural precedents, but assuming the migrant clan villages are based on vernacular precedent in the clan heartlands, it is interesting to speculate on the extent to which elements are transferred from these origins and to which elements constitute a specifically Hong Kong typology.

By comparison to the scale of Hakka settlements in Northeastern Guangdong and Fujian, the villages of Hong Kong are small; only Tsang Tai Uk (Sha Tin) is of a comparable scale, its architectural presence stemming from the uniform construction and detailing and comparatively intact state of preservation.

The elements of village planning, however, are present in many precedents, including notably the planned walled cities of China such as Datong or The Forbidden City in Beijing. Whilst there is no documentary evidence linking walled villages with these macro examples, they also feature a square walled moated enclosure, and a central axis with gatehouses and temple-shrines along it (note 33).

Funerary house models discovered in Guangdong province burial sites dating from the Han dynasty (206 BC–220 AD) include simple walled enclosures with corner towers. The evolution of the walled village can be traced to these precedents through the development of the courtyard house typology, progressing from northern to southern China to Guangdong.

The most common form of traditional Chinese townhouse consists of a gated walled enclosure with a central axis. Planning within this was hierarchical, the key spaces of central communal courtyards and halls being flanked by children’s rooms, servants and service areas to the side. At the rear would be the elders or parents accommodation. This arrangement finds parallel in the walled village gatehouse, central lane, and ancestors shrine. Funerary pottery house models confirm the typology, some with a fortress-like structure of enclosing walls. These precedents are characterised by their axial planning symmetry, order, balance and definitive spatial hierarchy, which can be traced to a Confucian world view that these attributes were essential to the regulation and order of family and society (note 34).

Axial planning: plan of Datong walled city; plan of a Beijing siheyuan courtyard house.

The large circular Hakka walled villages of the tulou type found mostly in Fujian and Jiangxi provinces emerged during the mid 18th century. The circular plan provided no obvious point of weakness from siege tactics such as undermining. Internally they are planned in a similar way to rectangular house complexes of the same date, with gatehouse, central halls and ancestral halls along a main axis, subsidiary rooms and stores around the perimeter. Whilst the circular tulou are today well-known through UNESCO designation and consequent tourist promotion, the Hakka simultaneously built villages of many types: round, square, rectangular, oval, semicircular and horseshoe shape, pentagonal and hexagonal. These configurations derive from various factors: clan dominance, potential for conflict, banditry and lawlessness, microclimate, topography, population pressure and demographics. The majority of the circular, and all semicircular, Hakka residential enclosures were built after 1800, and most were built during 1960-69. Square enclosures were also built throughout this period, generally in greater number, and with increasingly higher walls and fewer openings. The fortress-like weizi dwellings of nearby southern Jiangxi are a precedent closely matching early Han dynasty funeral house models, and whilst there is no evidence of historical connection, the persistence of this typology is relevant to any discussion of Hakka architecture (note 35).

Circular and horseshoe configurations incorporating axial planning: the tolou of Fujian and Jiangxi provinces, and a typical horseshoe plan found around Hongchang and Diaofang, Guangdong.

Notes:

33. Notes on walled cities derived from Ip (1995)

34. Notes on Confucian ideology derived from Poon (2009)

35. Notes on Hakka tulou derived from Knapp (2000)